- Home

- Hippolyte Mettais

Paris Before the Deluge Page 5

Paris Before the Deluge Read online

Page 5

Either because the countries were sufficiently well-known, however, or for some other motive, their itinerary was changed. Having arrived in sight of Egypt, they made an abrupt left turn, heading toward the waters of the Black Sea, through vast lands that were fairly densely inhabited, but furrowed in all direction by rivers, lakes and seas that were all connected, so deep and vast that they might have been taken for branches of the Atlantic Sea.

Until then they had scarcely paused on their route, in haste as they doubtless were to reach their goal. It was, however, five months since they had left Tehpuec when they entered the waters of the Black Sea, a vast sea of which we only know the extreme points today.

Until then their voyage had been untroubled. Sylax and Me-nu-tche had not noticed the passing of time, occupied as they were with philosophical and religious discussions, but Sylax had not yet made any progress in changing his friend’s mind, and Me-nu-tche, although he had not convinced Sylax either, was enjoying himself naively and as a benevolent friend, because his arguments had not yielded any ground.

The Atlantean scientists, for their part, had not been wasting their time; they had collected along the way all the scientific evidence in search of which they had set out. They had done so calmly and confidently, the sea having been kinder to them than they had any right to expect. Even the Black Sea of such sad memory had not troubled them.

On leaving that sea which, while changing its name, led them gradually into unfamiliar territory, on waves that were all the more dangerous because they to were little known, they were obliged to advance circumspectly.

That prudence was fortunate for them because, in spite of a few difficulties and even sustaining some damage, which dogged their paces in those terrible northern seas strewn with more-or-less hostile peoples and tribes, the Atlanteans were able to congratulate themselves for having navigated for more than five whole months without having lost a single man or even run any serious danger.

Thus, they were advancing with confidence toward the unknown to which they had been looking forward so much, and which their scientific imagination filled with all the riches of the unexpected.

That boldness was not unfortunate for them, and toward the middle of the sixth month of their navigation they found themselves in the heart of Europe, facing a vast island toward which they were rowing hard. There, however, torrential rain, as frequently occurred in that epoch, caught them unawares and stopped them.

A frightful storm blew up both above and around them. Thunder burst forth in all directions; submarine rumbles were heard in the deepest waters; then mountains of water were suddenly hurled into the air, with horrible explosions, threatening to engulf the two unfortunate vessels at any moment, which were bobbing like floating leaves. Several boulders, brought up from the depths of the abyss by an invisible force that was nothing other than that of volcanoes, fell at the very feet of the navigators, who thought that their final hour had come.

The darkness was almost continuous, and the island was no longer in sight; perhaps it had been flooded, perhaps swallowed up in the volcanic abyss.

“My friend,” said Sylax to Me-nu-tche, “God is punishing us for your incredulity.”

“Forgive me for being the involuntary cause of your misfortune, my poor friend,” replied the philosopher Me-nu-tche, “but I think it very bad that your God is punishing you for my sins, instead of extending mercy to me on account of your virtues.”

“God’s intentions are incomprehensible; let us worship them,” said the Buddha, squeezing his friend’s hand affectionately.

“If God’s intentions are incomprehensible,” Me-nu-tche retorted, smiling sadly at his friend, “why do you appear to want to comprehend them, in telling us that He intends to punish us? Why do you want the lightning to be unleashed arbitrarily from the hands of your God, volcanoes to open up beneath us like a fan, and God to move Heaven and earth vindictively to engulf an ant navigating on a wisp of straw? Why do you, a scholar, as everyone knows, not say to yourself: there are laws in nature that form and regulate storms, which make volcanoes burst forth, which inundate land and navigators-too bad for the unfortunates who find themselves in the path of those catastrophes?” And Me-nu-tche added: “I beg you, my friend to give up the impious habit of mistaking our appreciations for the will of God.”

Sylax was about to reply when several voices cried: “Land! Land!”

That horrible storm had lasted a week. It had brought desolation to the island that was in view, destroying all of its crops and flattening almost all the habitations. The sea, for its part, had invaded the soil for a considerable distance and made horrible ravines in its coast.

It was the land of the Teutchs.17

IV. The Islands of the Teutchs

The sky had suddenly become serene again; the sea was calm, as if it had not just flown into a furious temper. The Atalantean voyagers, still very relieved by the idea that they had escaped catastrophe, were beginning to render thanks to Heaven when they saw a host of small boats coming toward them manned by a multitude of tall, strong, Herculean, half-naked men with pale skins, blue eyes and abundant red-tinted hair tied up in a topknot.

They were the Teutchs. The Atlanteans watched the boats approaching without anxiety, for nothing indicated that they were manned by enemies. In fact, the Teutchs did not look ferocious and their mores were hospitable, but shipwrecked victims were not guests so far as they were concerned: they were prey that their gods had sent them via storms. To rescue them from the waves and take them to their island was to them, in consequence, simply a matter of salvage to their own advantage.

Thus, they put all kinds of care into conducting that providential cargo of Atlanteans to a place of safety, and did so with perfect cordiality, even though the two large vessels were difficult to guide to the shore.

The Atlanteans marveled at that kindness, which they had not expected to find in a country so disconnected from the rest of the world, and they began blessing God for having directed them to a land where science would doubtless have much to harvest.

Their illusion did not last, however. It did not take them long to perceive that they were no longer human beings to the islanders but booty: slaves.

The pious Sylax was not disconcerted by this discovery; it matters little to him to whom he preached his doctrine; he had high hopes of convincing his listeners.

Me-nu-tche was not so easily consoled, for he could no longer see what advantage he was going to obtain from his voyage to Europe. The most obvious thing to him was that he was a prisoner, and also a slave.

Apart from the inhuman retention of considering any shipwreck victim as legitimately acquired wealth, however, the Teutchs were not people to be feared. They were neither savage nor cruel, and even though their civilization was essentially different from that of the Atlanteans, there was a certain wisdom and sensitivity in it.

It was considered a mark of civilization among them to be able to tie up their hair artistically on top of the head, to present the forms of bare limbs graciously, to shoot accurately at an enemy with a bow, and to sing in a loud and sonorous voice about the pleasures and dangers of the sea and incomprehensible and uncomprehended memories of the fatherland. Although they only researched in history what was happening around them, and in geography that of their island and the neighbors with whom they were often at war, and in astronomy that which their highly experienced eyes told them, they were, on the other hand, just in their social relationships, generous in regard to one another, habitually honest and full of deference for women.

That civilization surely had some merit.

In the epoch when the Atlanteans disembarked, their government was headed by leaders that historians call kings, doubtless for want of a more accurate term, because it would be difficult to classify the royalty of the Teutchs, which was neither absolute, nor constitutional, nor democratic. It was scarcely more than a stewardship.

It was, at any rate, elective; it was always given to the bra

vest, the most learned or the most eloquent, and only for a year, with the proviso that the same steward-king could continue indefinitely so long as his services were acceptable.

There was no instance in the memory of the Teutchs, when the Atlanteans arrived, of any previous king having tried to render himself independent, omnipotent, or the proprietor of his fellow citizens to the point of administering them as he wished and bending them to his will.

At any rate, their power was not great; the military leaders were as powerful, and more so, and the united people were more powerful than anyone.

Everyone, moreover, held to his rights: the rights of any people that have not forgotten in dreams of egotistical ambition the principles of society, state and government. All public affairs were treated as comitias to which everyone came armed, not in order to fight and make force prevail over reason, but to applaud or criticize the proposals of the king by striking their weapons in a certain manner.

The king, therefore, never imposed any law or issued any decree, but made proposals, and the people, who were not a population of courtiers, gave their opinions without any hesitation or oratory precaution, which was always accepted without rancor and executed loyally, even by those opposed to it.

Everyone went into combat among the Teutchs, even old men, women and children. Their tactics were not a progressive science, but merely a tradition, a custom. It consisted entirely of courage. There were no studies or military exercises. There were, however, leaders, and leaders of great value.

It had remained in the memory of the Teutchs that in a remote era their island had been in great peril, assailed by a host of enemies of unknown origin.

A caravan of emigrants came from far away, from a land of which the entire world had forgotten the name, and had been received very hospitably some time before, on the orders of a divine oracle. Every man in that caravan was a hero; he paid for his hospitality by fighting so bravely and so successfully that the enemy host was dissipated and the island freed from them permanently.

Thanks were rendered to Heaven; the generous defenders were installed from that day on at the lead of the Teutchs’ militia, with all the privileges of a noble corporation, uniquely charged with providing leaders for the protection of the country and wars undertaken abroad.

That corporation did not die with time; it prospered, grew and became, veritably, the unique force and glory of its adoptive country, without ever degenerating.

It was still brilliant when the Atlanteans arrived, by virtue of its position on the island and its courage, which had not degenerated relative to that of its ancestors. Its interests, moreover, did not differ from those of the rest of the Teutchs, with which it was perfectly identical, its primitive nationality having been almost forgotten—and, indeed, the blood of the two races had intermingled.

That corporation was known as the corporation of the Pah-ri-ziz.

Another corporation, no less important, was that of the Priests, whom the Teutchs called the Galls. Their functions consisted of rendering justice and practicing the ceremonies of religion during public meetings.

The great divinity of the Teutchs was the Night, so they counted their months and years not in days but in nights. They did not raise temples to her; they rendered their homage in the densest parts of their forests.

Those mores lasted a very long time, and we still discover them in part among the descendants of the Teutchs, the Germans,18 in the second known antiquity. There would not have been anything alarming about them for the scholars of Atlantis had they not been reduced to slavery—but a slavery that was, in fact, quite mild.

Sylax found himself free enough to preach, and he did so courageously, even though he was preaching in a desert.

Me-nu-tche and the other scholars were solely occupied in conquering, by the graciousness and utility of the services they rendered, the esteem and affection of their masters, who were well able to appreciate them, and who all, in truth, while not forgetting their rights, responded to the favors with a grateful amity.

The Pah-ri-ziz above all, as well as the Galls, who were the most learned and the most benevolent men, were very devoted to them. One small event, quite simple and natural, but which was to have decisive consequences for everyone, rendered them brothers.

Among the Teutchs, as among several other peoples of antiquity, it was customary, when a father wanted to marry off his daughter, to invite all the potentially acceptable suitors to a feast. The young woman would not attend the meal, but she would arrive at the end carrying a cup full of wine, which she would offer to the one she preferred.

Now, in those days, one of the Pah-ri-ziz chiefs, Lutetius, held that betrothal feast. He was Me-nu-tche’s master. In his capacity as a slave, Me-nu-tche was to serve the guests and entertain them according to their wishes.

The meal passed as usual, and when it was finished, the chief’s daughter, Lutecia, appeared. In accordance with a custom particular to the Teutchs, however, at that moment, before the young woman’s choice was expressed, every guest had to sing a song adapted to the occasion. It was appropriate at a betrothal feast to sing about one’s notable feats or those of one’s ancestors, national or martial songs, ballads or ancient legends, but never anything frivolous.

The guests of the Pah-ri-ziz equipped themselves with all the enthusiasm of great desire, for each one was singing to impress the host’s beautiful daughter.

The musical contest was always concluded by a song from the master of the feast, but Lutetius excused himself. Turning to Me-nu-tche, he said: “Slave, you have a fine voice; sing us, in order to replace the voice that I lack this evening, a song from your country.

Me-nu-tche was, in fact, a fine singer even in Atlantis; his song was bound to seem divine to the Teutchs. The impression it produced was, in fact, indescribable. He sang:

Uranus was a good king,

Who came down to earth.

To do what?

To ask us the question

Why do you want a king?

That ballad, which had a lot of verses, was as old as Atlantis. It was a popular song from no one knew where, but which was evidently a song of governmental transition, probably the transformation of a monarchical government into a republican government.

The slave’s voice had seduced all the guests, but the words, above all, had thrown them into a profound emotion, because they all knew the song, and they had all sung it many times in their life.

No one among the Pah-ri-ziz knew, any more than the Atlanteans did, where the song came from or who had written it, but the Pah-ri-ziz sang it as the national song of their ancestors—ancestors about whom they knew nothing. They had been in the land of the Teutchs for such a long time, perhaps many centuries, that the land in question was their only fatherland. All their history was there, all their projects and all their interests were there, but there was a tradition among them—and we already know that their corporation had not originated on the island—that their forefathers had once arrived there as refugees from their homeland. What homeland and in what era they did not know; they had only retained by way of history the fact that their ancestors had saved the island from its enemies, and Me-nu-tche’s song.

But their history had just been revealed completely to their eyes. Their national song was the national song of Atlantis; therefore, Atlantis was their original homeland! Therefore, the Atlanteans were their brethren—and they had made them their slaves! Horror!

All the Pah-ri-ziz threw their arms around Me-nu-tche, shedding tears of joy. Lutecia presented him with the betrothal cup.

That news spread with lightning rapidity throughout the island. Instantly, the slavery of all the Atlanteans was ended; the law that rendered all castaways slaves appeared unjust, and was abolished that same day.

Joy was at its peak among the Atlantean scholars, who no longer saw their slavery as anything but a piquant episode to recount in the future. They conceived once again the pleasant hope of pursuing, even more fruitfully th

an before, the scientific results to which they had aspired. From that moment on the Teutchs became precious auxiliaries for them.

In fact, they found on the island all the assistance necessary to their expedition. Their project had not changed; it was still to explore that region of the seas, to go deeper and deeper into the lands of Europe, even though they had no certain notion of the route they ought to follow.

The Teutchs were quite incapable of informing them. They were only familiar with a few islands in the region, which they devastated from time to time, in order to prove their superiority over their neighbors. All the seas that lay beyond—and all the lands they contained, if any—were merely uncrossable regions so far as they were concerned, gulfs feared by the most skillful navigators or deserted lands populated exclusively by ferocious beasts.

The Atlanteans smiled at these lugubrious depictions; they only persisted more tenaciously in their voyage.

They departed, therefore, accompanied by a few bold Teutchs and a few adventurous Pah-ri-ziz. Lutecia did not want to be separated from her spouse, but she promised her father to come back as soon as possible. Me-nu-tche and the entire maritime caravan also promised, because they hoped to do so.

V. The Shipwreck

The first days of that navigation were very pleasant. They were employed in visiting the islands nearest to that of the Teutchs, especially the isle of the Sequans,19 which was quite large, but diminished by a river that wound around it like a serpent, in such a way as to create an island within the island. The portion of land that was between the river and the sea was uninhabited and uninhabitable because of the continual inundations that kept it submerged for part of the year.

The studies to be made of that island were neither long nor difficult. The Sequans, like the other European peoples of that time, had no written history, nor any monuments other than the huts that served as their habitations and a few stones placed in a certain manner in order to have some significance in the narration of a memorable event.

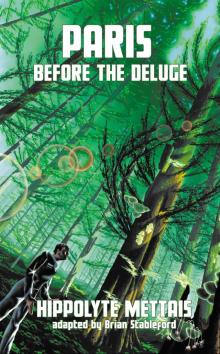

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge