- Home

- Hippolyte Mettais

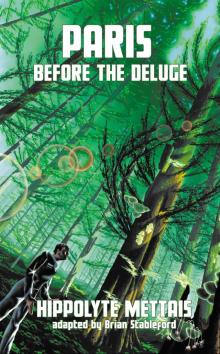

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge Read online

Paris Before the Deluge

by

Hippolyte Mettais

translated, annotated and introduced by

Brian Stableford

A Black Coat Press Book

Introduction

Paris avant le Déluge, here translated as Paris before the Deluge, was initially published under the signature “Dr. H. Mettais” in 1866 by the Librairie Centrale. It was the author’s fourth publication from the publisher in question, directly following L’An 5865, ou Paris dans quatre mille ans (1865; tr. as The Year 5865),1 to which it is a companion-piece. Whereas its predecessor had offered a broad description of the world four thousand years in the future, paying particular attention to the fate of the city of Paris—by then in ruins and the subject of strange legends to which the civilized inhabitants of the new world lend little credence— Paris avant le Déluge offers an image of the world more than four thousand years in the past, paying particular attention to a city once located where modern Paris stands, but of which nothing survives, following its catastrophic destruction, save for a few fragments of legend whose significance is no longer understood. The two speculative novels also form a trilogy of sorts with the naturalistic quasi-autobiographical novel Souvenirs d’un Médecin de Paris [memoirs of a Parisian physician] (1863), which deals with the Paris of the present day.

Although Paris avant le Déluge closes the trilogy in question in terms of the order of publication, at least some of its text might have existed prior to its finalization with that intent. There had been an earlier phase to Mettais’ literary career in the early 1840s, when he published two melodramas of his own and a third in collaboration with a once-popular writer of works of that sort, Georges Touchard-Lafosse. A long gap of more than twenty years separated that set of three from the later set, although Mettais did published one non-fiction work—a political pamphlet—in the interim. The latter group is far more ambitious in literary and philosophical terms, and by that time, Mettais probably regarded his earlier ventures as juvenilia. The formulae of the conventional melodrama in which they dabbled are, however, not entirely absent either from L’An 5865 or, more particularly, Paris avant le Déluge.

The third and longest of the three parts into which the narrative of Paris avant le Déluge is divided deliberately recasts the substance of conventional early-19th century French melodrama within the pseudohistorical framework established in the first two parts. It reads as if it might be an adaptation of an earlier manuscript telling a story set in the familiar city of Paris before and during the 1789 Revolution, which was belatedly adapted to its new framework in order to transform it into something markedly different. Whether or not that is the case, the adaptation does indeed achieve such a transformation, offering an exceedingly odd admixture of the exotic and the familiar—in terms of its plot, the very familiar, given that it toys with one of the standard clichés of contemporary melodrama.

The cliché in question was dubbed by Paul Féval in Les Habits Noirs (1863; tr. as The Parisian Jungle)2, who was perfectly willing to employ it even while treating it sarcastically, as the “cardboard baby,” because dramatic versions of it tended to introduce the character in Act One as a babe in arms—usually played, therefore, by a doll—mislaid by a mother, sometimes stolen, but often simply lost or given away by virtue of social inconveniences surrounding the birth. The character then reappears in Act Two as a young adult whose birth is surrounded by a mystery, which is ultimately to be solved in the denouement by courtesy of what Féval calls “his mother’s cross”: some trinket lost along with the baby whose eventual recognition, usually by the mother, leads to the revelation of the character’s true identity, on which some kind of inheritance usually depends.

Sanctified by the doyen of all Romantic writers, Victor Hugo, who employed it with regard to Esmeralda in Notre-Dame de Paris (1831; often known in translation as The Hunchback of Notre Dame), the melodramatic potential of the formula was mined so assiduously by the feuilletonistes who began to flourish in the 1840s that by the 1860s, when Féval satirized it while still making the most of it, it had become rather difficult to refresh or recomplicate. Versions involving two “cardboard babies” had become commonplace, and Mettais’ move in increasing the number to three might have smacked of desperation had the story told in the third part of Paris avant le Déluge been presented as an account of tribulations suffered in the year 1789 rather than the third millennium B.C. Shifting the cardboard baby formula more than four thousand years in the past, however, was an unprecedented imaginative flourish of considerable boldness and even more considerable eccentricity.

It is also possible that the frame into which the cardboard baby narrative was shifted, if that is really how the story was put together, was not built specifically for that purpose, but began as a separate work of pseudohistory that petered out because the narrative ran out of steam and stood in dire need of refreshment itself. Whether the subsequent combination, however it came about, eventually leads to a fruitful synthesis of the thesis and antithesis is open to doubt, but the alchemical fusion is certainly not without interest. The juxtaposition transforms the significance of the Biblical Deluge as well as the significance of the 1789 Revolution, adding a flamboyant ironic twist in the process to Madame de Pompadour’s oft-quoted flippant prophecy, “Après nous, le Déluge,” which seemed to many later writers an apt summary of the decadence and fate of the ancien régime.

Although it certainly does not constitute an example of “decadent style,” as defined by Théophile Gautier, Paris avant le Déluge is very preoccupied with the idea of historical decadence, which was an important topic of discussion in nineteenth-century France. Historical theories promoting the idea that civilizations had a natural life-cycle analogous to that of individuals, in which grandeur and power were inevitably transitory, leading to decline and decay—first popularized in France by the Baron de Montesquieu in the 18th century—were reinforced and revitalized by archeological investigations, particularly those carried out in Egypt in the wake of Napoléon Bonaparte’s campaign there. They were also combatively counterweighted by the development of another 18th century idea, the theory of progress: the idea that the advancement of science, and the consequent development of new technologies, was the principal dynamo of social change, facilitating a process of incessant improvement, or “perfectibility.”

The stark opposition between the hypothesis that contemporary French civilization was doomed, after a long period of growth and increasing magnificence, to decline and destruction, and the hypothesis that, unlike all the failed experiments that had preceded it, but from which it had learned, might endure until it obtained a kind of perfection was thrown into much sharper relief by the 1789 Revolution and its aftermath. The Revolution had been represented by its proponents as an inherently progressive process, and also as a cleansing process reacting against and providing a solution to the alleged decadence of the ancien régime. When it was followed by the Empire and the Restoration, however, and even more so when the Restoration was followed by the July Revolution of 1830, the revolution of 1848, and the coup d’état of 1851 that established the Second Empire, the picture became very confused.

Supporters of revolutionary politics still insisted on representing their ideas and their efforts as progressive, and as an antidote to symptoms of decadence, while their opponents stigmatized them as a hindrance to progress and as symptoms of decadence in themselves. That was the ideological battlefield on which Mettais pitched his philosophical tent, in L’An 5865, Paris avant le Déluge and their naturalistic predecessor, extending Montesquieu’s hypothesis regarding the life-cycle of civilizations onto a far broader temporal stage, where it almost becomes a myth of eternal

recurrence.

One of the major themes of L’An 5865 is the unreliability of history, especially at the interface where oral tradition is translated into documentary form, when a confused conglomerate of memory, folklore, legend and myth is initially concretized by writing. In L’An 5865 the reader is invited to appreciate many of the misconceptions that the historians of the hypothetical future have about our era, hence cultivating an understanding of how such misconceptions come about, assisted by the ravages of time, and perhaps also geological upheavals, which routinely obliterate all but a few vestiges of a dead civilization’s writings and monuments. In Paris avant le Déluge the perspective is inverted, as the reader is invited to wonder how the vestiges of long-past civilizations that have survived earlier geological upheavals might have been misinterpreted to form our mythology of prehistory.

Writing in the 1860s, Mettais had little idea of the geological chronology that we have now refined with the aid of radioactive dating methods. He was aware of the work of geologists, archeologists and paleontologists like Charles Lyell, Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Georges Cuvier, whose work had cast severe doubts on the chronology of Biblical scholars like James Ussher, famous for dating the creation of the world to 4004 B.C., but the question of how far that chronology might have to be extended was still very much open to question. Although the geologist Benoît de Maillet had suggested a figure of two billion years, most estimates were much more restricted, only dealing in hundreds of thousands, or even tens of thousands, of years. Much depended, of course, on the notion of how the geological changes whose evidence remained in the strata had occurred, and debate was still fierce in the 1860s between “uniformitarians” like Benoît de Maillet and James Hutton, who thought that slow processes like erosion and sedimentation were primarily responsible, and “catastrophists” who put the primary responsibility on violent volcanic activity and inundation. The latter had the upper hand, because they not only had the Biblical Deluge on their side, but also the esthetic appeal of melodrama; although science, as time went by, came down very firmly on the other side, the literary dice were always loaded in favor of fire and flood.

The catastrophists not only had the Biblical Deluge as a trump card, but also the Deluges featured in various other mythological sources, most notably the Epic of Gilgamesh and Greek myths featuring Deucalion, both of which were known to Mettais, although the former, discovered in 1853, had not yet been translated. Catastrophists also had a similar, if somewhat more problematic, trump card in Plato’s accounts of the island of Atlantis, briefly mentioned in his Timaeus and more elaborately described in the fragmentary Critias, the latter being all the more intriguing because no one has any idea whether a longer version ever existed. Plato, the great pioneer of exemplary fiction designed to illustrate and dramatize philosophical notions—what Voltaire called, when he repopularized the method, contes philosophiques—had, of course, invented the idea of Atlantis himself, as a potentially useful means of dramatizing a design for an ideal society, and represented it as an item of secret history by way of a strategic literary device. From one point of view, the device in question has been fabulously successful in generating plausibility, although it is probable that Plato would have been horrified by that “success,” considering that it was causing his readers to miss the point entirely (which, if, in fact, he never completed the Critias, might be why he abandoned it).

It is not entirely clear from a superficial reading of the main text of Paris avant le Déluge how seriously Mettais took the story of Atlantis, although the lengths to which he goes in pretending to take it seriously—especially in his pseudoscholarly footnotes—are strongly suggestive of a sarcastic literary device; it is, of course, the most blatant liars and practitioners of tongue-in-cheek sarcasm who strive most ostentatiously to pose as truth-tellers. There is, however, a highly significant clue in the introduction he provided to his novel, even though it does not address the question of Atlantis directly, presenting instead an argument related to the Biblical myth of the Deluge, attacking the issue of how seriously the account given in Genesis should be taken. The conclusion of the argument, unsurprisingly, is that it ought not to be taken too seriously, and that the chronology it contains needs to be extended if it is to be made compatible with modern geological evidence, but what is more interesting is the form of the argument supporting that contention.

Having dismissed as patently ridiculous the idea that Genesis is the word of God, for whom Moses merely served as an amanuensis, Mettais asks us to consider Moses’ motive for writing the book. Given Moses’ objectives and problems in leading the Children of Israel out of Egypt, Mettais asks, what was his purpose in writing Genesis for them? He then goes on to offer a logical account of what that purpose must have been, and how, in consequence, the story of Genesis ought to be regarded—essentially, as propaganda rather than history. He does not ask the same question about Plato’s invention of Atlantis, but one is entitled to assume that he would have answered it in a similar fashion. Nor does he raise the question in respect of his own book, although he is surely inviting the reader to do so. The vital question to be asked in respect of Paris avant le Déluge, therefore—in the author’s own estimation—is not the question of whether it is rationally plausible as a conceivable account of prehistory, but what the author’s purpose was in writing it, and what the philosophical objectives are of his invention.

Part of that purpose was, of course, to expand Mettais’ ongoing fictional consideration of Paris as a key example of “civilization,” and the fact that, in order to do so, he blithely invented a second Atlantis to partner Plato’s, is perhaps equally significant in assisting the measurement of how far his tongue was in his cheek. If three cardboard babies are to be reckoned better than two, two Atlantises are surely better than one, especially for an author whose literary ambitions stretched over thousands of years while everybody else was dealing in mere hundreds, if they were bold enough to attempt any expansion at all.

In fact, Mettais was rather restrained in his invention of a colony of Plato’s Atlantis; several previous scholarly fantasists, apparently writing in all earnestness, had moved the “actual” site of Plato’s Atlantis all over the globe in an attempt to reconcile it with various items of historical and geographical data and their own ideological concerns. The Swede Olof Rudbeck, for instance, had written a treatise in 1675 “proving” that Atlantis was really Sweden. The Comte de Buffon, whose monumental Histoire Naturelle (1749-88) was one of the key French works challenging Biblical chronology, suggested in 1746 that the “real” Atlantis was probably in the vicinity of Sicily in an era when the Mediterranean was dry land.

The most important of these innovators by far, however, from Mettais’ point of view—the only one he cites in his footnotes—was the French astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly. Bailly’s Histoire de l’astronomie ancienne (1775) supplied Mettais with an argument that he uses in his introduction, to the effect that astronomical records conserved in China and India provide convincing proof of the fact that astronomers, and hence the world, must have existed long before 4004 B.C. Bailly does not stop there, however; he went on in subsequent works to develop an extensive theory of racial emigrations occasioned by climatic shifts, developing an elaborate argument in Lettres sur l’Atlantide de Platon et sur l’ancienne histoire de l’Asie (1779) to “prove” that Atlantis was actually Spitzbergen in the Arctic Ocean—a notion that Mettais wisely ignores, as it does not suit his purpose, although he is obviously not unsympathetic to the underlying argumentative method.

An inveterate reprocessor of myths, attempting to find the “underlying truth” beneath the supernatural icing, Bailly also credited Spitzbergen/Atlantis with an inventive astronomer-king named Atlas, the supposed inventor of the terrestrial globe. Mettais also introduces an Atlas into his story, but in a much more modest role. Bailly was one of Voltaire’s many correspondents, but never contrived to convince the great skeptic of the accuracy of his deductions. More pertinent

ly, with regard to Mettais’ novel, Bailly was also one of the prime movers of the 1789 Revolution, presiding over the instigating Tennis Court Oath, and serving as Maire of Paris from 1789 to 1791, when he fell from favor, ultimately losing his head during the Terror. Again, Mettais is more restrained in his invention, refusing to allow his great scientist Chephren to participate in the Revolution in the Parisian Atlantis, in spite of his democratic sympathies, but making him a reclusive ark-builder instead.

Given this historical context, it is easy to appreciate that while Mettais’ particular recycling of the myth of Atlantis was boldly innovative in literary terms, it was conscientiously moderate by comparison with contemporary scholarly fantasy, the latter typically being far more reckless and intellectually irresponsible than literary endeavor. This is because, like Moses in Mettais’ representation, writers of fiction often have a clearer idea of their purpose, and hence of their rhetorical strategy, than scholars, who are more likely to be blind to their own ideological prejudices and perversions. Mettais’ novel is exactly contemporary with Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg’s Monuments anciens du Mexique [ancient monuments of Mexico] (1866), whose interpretation of the relics in question waxed lyrical about the “proof” they provided of the role of Atlantis in providing links between the cultures of Central and South America and the civilization of classical Greece and Rome, and thus helped to inspire such classic scholarly fantasies as Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882) and the Atlantean component of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical doctrine. Although it remains a matter of opinion as to whether Mettais or Brasseur was the more ingenious inventor, Mettais, if one analyzes his rhetoric correctly, was surely the more clear-sighted.

Although Mettais was far from famous in his own day and was largely forgotten thereafter, Paris avant le Déluge does stand, whether by virtue of influence or pure coincidence, at the head of a significant tradition of French Atlantean fantasy, rich in adventure stories and melodramas, which often have a significant philosophical edge. Mettais’ speculative fiction was contemporary with the early works of Jules Verne, who also imported the Atlantis myth, albeit peripherally, into Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (1870; tr. as Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea). Verne’s example was undoubtedly more crucial in stimulating the production of such works as Atlantis (1895; tr. as The Crystal City under the Sea) by his sometime collaborator “André Laurie” (Paschal Grousset) and L’Atlantide (1919; tr. as The Queen of Atlantis) by Pierre Benoît, but Les Atlantes [The Atlanteans] (1903) by P.-B. Gheusi and Charles Lomond, and Les Pacifiques (1913; tr. as The Pacifists) by Han Ryner3, are closer in spirit to the modified Platonic tradition of Mettais’ novel.

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge