- Home

- Hippolyte Mettais

Paris Before the Deluge Page 3

Paris Before the Deluge Read online

Page 3

What, in fact, did Moses want? We have said it: to make a free people of his scattered and enslaved brethren.

What did he have to do to accomplish that great task, worthy of a veritably inspired man?

Well, my God, there was nothing to do except what he did.

The God of Moses was Jehovah, the God of the patriarchs and the antediluvian pastors as well as the Israelites who came after the deluge.

But had the Israelites conserved their belief intact in the midst of their various peregrinations and during the long sojourn they spent among the polytheistic Egyptians? Had not many of them renounced their mores to embrace those of their masters, and their religious aspirations in order only to live with those they saw elevated around them every day?

How, then, could a people be made with elements so disparate, badly seated, to say the least. A people is a society with the same views, the same desires and the same perspective; it is a union of common interests. All the efforts of the great liberator had to be directed to unifying the views of the Hebrews, exciting the same desires, presenting the same perspective to them all.

We can, in fact, see him completely occupied in making his belief the belief of all, in raising up in the minds of people imbued with prejudices and little versed in the mysticism necessary to religion, the God that he worships and wants everyone to worship, the God that has chosen him for His support, his King and his Legislator, the great, omnipotent God who created the universe with a single Word, the terrible God who punishes those who do not obey Him and who laughs at His prophets with a universal deluge.

That is why Moses wrote his book; and his book was perfect, because it was the belief that bound those people together; it was the same religion, the same worship, the same laws; it was the same memories of the past, the same hopes for the future. In sum, that book created a people.

Moses’ goal was thus attained. What need was there, in consequence, to look any further for irrefutable monuments and reliable guides, to establish a history such as we understand history today? What did the chronology of times past and other peoples matter to him? What did the rest of the world matter to him? Did he worry about it? Did he not have his own belief, his own chronology and his own history, which served his objective well? Did he want to pass himself off as a scholar, to discuss the dates, the opinions, the religions and mores of others? Did he want to acquire the merit of a historian, who desires to instruct posterity as well as and more than the present, by leaving it his science, the science of a scrupulous man who only writes what he has seen or checked against irrefutable monuments?

No! His aim was greater; he wanted to save his brethren and create a people.

Oh, that goal might well make one forget a few chronological exactitudes; that goal might well absolve a writer of a few hazarded assertions that science and history do not sanction; that goal might well cause one to pardon a excessive severity—which was, after all, only the severity of a leader who sees his institutions imperiled, or a conqueror who is drawing in his wake nearly a million human beings in need of shelter and bread.

That goal might well also relieve him of the accusation of frivolity of belief in recounting, without reliable testimony, the great event of the universal deluge. Do not all the ancient peoples speak of it?

They do not mean a universal deluge such as we understand it, but a deluge that seemed so to them, so frightening, immense and devastating was it. All religions have consigned it to their records, and Moses, who was brought up in Pharaoh’s court, who had lived for many years among a numerous, educated, largely civilized people—the people of Egypt—had a perfect right to repeat what he had heard said.

We would be wrong to ask of Genesis more than it wishes to give us; we would be wrong to weigh those words as misers weigh gold, torturing them in order to reconcile them with the verities of modern civilization. We ought to take that book, that admirable book, for what it is, for what it really is, while blessing it for the good it has produced.

It will still remain to us as a precious monument, if not of the true history of the antediluvian peoples, at least to the popular traditions of the epoch and to the savant and energetic skill of a great man.

As for the exact history of other peoples of the time—the general, philosophical and scientific history of the worlds as it was then—we must seek it elsewhere; for Moses was not the only person to write in those days, and his ancestors and his nation were far from being the most civilized in antiquity.

What he does not tell us, the Atlanteans, the Hindus, the Egyptians and even the Greeks tell us in showing us the genealogy of their kings, the eras and chronological dates of their peoples, inscribed in their ancient documents, in writings of every sort, on their monuments and in the memories of their traditions.

Now, the history of those peoples reveals to us that before the Hebraic deluge the earth was very populous. They tell us that in those times there were simple and primitive peoples, that there were semi-civilized peoples and others that were savage and barbaric. There were also civilized peoples, and even a very advanced civilization, for one sees them already practicing the sciences the most difficult for the human mind, devoting themselves to the longest and most complicated calculations of the most advanced astronomy.

Well before the deluge, astronomical problems had been resolved that we have only resolved after long centuries of civilization, in spite of all the scientific baggage that reached us from various directions and which served to elevate our knowledge greatly. I shall only report one example, which seems to me to be utterly conclusive.

The solar years and the lunar months are, as everyone knows, in a perfect and exact relationship thanks to the sagacity of our astronomers. But our astronomers were only able to arrive at that perfection of calculation by recording with scholarly attention the astronomical events of a period of six hundred years. That was our Julian period; scholars call it the lunisolar period, or period of six hundred years.9

Now, according to the historian Josephus, whose word is well-founded, that lunisolar period, one of the most beautiful conquests of our modern astronomy, was known before the deluge, and by even the patriarchs.

Thus, science and civilization existed on the earth in those days!

Thus, I shall add, seizing that fact, which has fallen into my hands to furnish me with a proof for which I was no longer searching of the facility with which Moses treated the chronology of early times, the period of sixteen hundred and fifty-six years that Genesis caused to elapse between the creation of the world and the deluge, is impossible, for, as Buffon says: “in order to suspect the lunisolar period of six hundred years, [antediluvian peoples] would have required at least twelve hundred years of observations; in order to ensure themselves that it was a certain fact it would have required more than double that, which already makes, therefore, three thousand years of astronomical study…and must not those three thousand years of astronomical observations have been preceded necessarily by a few centuries in which science was as yet unborn?”

It is evident, in consequence, once more that the book of Moses ought not to be taken literally everywhere and forever.

It is evident, as well, that if I show the earth inhabited and civilized before the deluge, and I have competent authorities familiar to everyone for it, and that if I say that the deluge was not universal, I can be worthy of trust in spite of Genesis—or, to put it a better way, to make it clearer, in spite of the interpretation that a few people give to the story of Genesis when they take it too literally.

And in fact, I conclude definitively and frankly that the deluge was not universal, and I shall interpret what Genesis says logically and scientifically.

General history, moreover, will still be here for us.

I know full well, and I admit once again,10 that in history, it is necessary to know when to stop.

However, although I do not have a complete confidence in the stories it tells us, and which it is often as well only to accept

subject to verification, it is necessary to recognize that there are points that one cannot call into question, certain reference-points that we ought not to forget if we want to know the truth.

Those reference-points are chronological dates.

If, therefore, the deluge occurred sixteen hundred and fifty-six years after the creation of the world, two thousand three hundred and forty-eight before our era, and if it was universal, what became of the peoples who inhabited the world at that time?

They were buried beneath the waters, Moses says; they all perished, except for Noah and his children.

That assertion is very strange, because it is in precisely that epoch that the history of various peoples emerges from uncertainty and darkness to enter into the ways of the known.

The history of China presents us with a few shreds of the marvelous a further three thousand five hundred and sixty-eight years before our era, but in the year two thousand six hundred and thirty-seven it establishes its dates with certainty and continues to the present day without interruption.

The history of Egypt is certain two thousand four hundred and fifty years before our era.

India, Greece and, above all, Atlantis, were known before the deluge. We have the genealogy of their kings, we have authentic monuments of them, and we have the chronology of their peoples. Now, their peoples appear to us to have been so numerous and so civilized in the days that followed the epoch indicated for the deluge that it is impossible to admit that they only had Noah and his sons for forefathers.

At any rate, it is not my intention, believe me, to issue an indictment here against Moses and his book.

Moses was a great man, one of the greatest geniuses that antiquity produced.

His book is a book above all praise. I admit that with conviction.

The errors that he advances are the errors of the time. The truth of one epoch is often the error of another; one ought to rectify it, not criticize it; that is, in any case, in the designs of God, who does not enable human intelligence to march with giant strides.

I only want to say one thing, and I repeat it: that the Hebraic deluge was not complete and universal. That is sufficient for my objective, for it cannot only be via that glimpse of ancient times that the historical episode has reached us that I want to recount, regarding the two Atlantises, that of Africa and that of the Pah-ri-ziz.

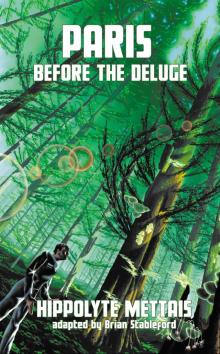

PARIS BEFORE THE DELUGE

PART ONE

THE AFRICAN ATLANTIS

I. A Bird’s-Eye View of the Island

Atlantis was an island of great celebrity in remote antiquity; its origin and even its life are lost in the night of time. The ancients say that it was the most anciently inhabited land.11

It was situated on the west coast of Africa, in the midst of the waters that, presumably taking their name from it, were called the Atlantic Sea.

It was, the ancient historians say, three thousand stades long by two thousand wide—which is to say, about a hundred leagues by fifty, approximately the size of France.

Its population was immense, swelled by that of small islands that surrounded it in great number, over which it reigned and which linked it to the neighboring continent.12

Atlantis extracted from its own soil almost everything necessary to life: wheat, wine, fruits, the most sought-after perfumes, fabrics, precious kinds of wood for construction of luxury and furniture. All minerals were abundant there, including gold, silver, iron and orichalcum, a precious metal of which only the name is any longer known.

Thus, its commerce was immense, but it was praised above all for all its beauty and the mildness of its climate as well as its admirable fertility. The earth produced two crops a year there, watered as it was in winter by benevolent rains and in summer by canals that refreshed all the fields.

The cities were splendid. They had magnificent temples filled with golden statues, and decorations of the same metal and of orichalcum, magical palaces, expertly constructed ports and numerous harbors for vessels.

Its metropolis, most of all, was indescribably beautiful and wealthy. It was surrounded by profound ditches filled with water, over which a large number of bold bridges had been projected. Broad canals departed from there to extend throughout the island, greatly facilitating communications. Those that opened to the sea were broad enough to allow access to triremes. A host of other smaller canals served for the transportation of people and merchandise.

Atlantean warriors were reputedly heroic; their boldness and good fortune were universally feared.

The civilization of Atlantis arrived in due course at a height that astonished the world of that time, all of which was warmed by its benevolent radiation, which expanded everywhere.

What science there was in Egypt, Phoenicia, Chaldea, India and China—among all the oldest peoples, in sum, whose surprising knowledge we still admire today—came from Atlantis.

Like all peoples, the Atlanteans had their period of infancy, their period of growth, that of degeneration and their end.

The period of infancy was undoubtedly simple; a people is not born in splendor and opulence, like the son of a great lord. But it was wise, apparently, and eminently wise, for it imposed its beliefs and their worship on others.

The theogony of the Atlanteans even had the rare good fortune to become almost universal, to survive its authors for many centuries after their disappearance and to make polytheism the religion of all civilized peoples even in recent times. The greatest gods of ancient Greece and Italy came from Atlantis. It was in Atlantis that Uranus, Neptune and Atlas—all the familiar gods and heroes of mythology, in fact—reigned successively, and of whom we have been taught to consider as myths, although a serious history says otherwise.

Whatever the first theology of Atlantis was, however, it was not the last; at least, it was not the only one prior to the catastrophe that carried them away.

Like many peoples, the Atlanteans experienced over time the need to modify and even change their beliefs, rendering them more subtle and more worthy of the philosophy of scholars making progress.

We should not criticize them for that, for those days were not the least glorious of their life. The debates were lively, even bitter, it is true; but from their collision a higher expression of religious philosophy eventually emerged: Brahmanism, which lent its dogmas and its doctrine to more than one religion, and gradually spread through almost all the peoples of the Orient, into China and India, where it still endures, even though it appears to have been annihilated for centuries.

If the debuts of the Atlantean people were happy steps and giant strides, history does not leave us unaware of the fact that its period of growth also shone with an unprecedented gleam, and that its power eventually became immense.

But was it happy in those days? Were there political revolutions in that beautiful country?

One cannot doubt it—and that should not surprise us on the part of people who had achieved such a great civilization, for the power of their kings cannot have been in harmony with the rights of the citizen. The power of kings over men was absolute and unbridled, for it was also absolute over laws. The law was nothing other than the will of the god Neptune speaking in his temple, and therefore theirs, the god always speaking, undoubtedly, as they wished.

What is astonishing, in consequence, in the fact that the people eventually thought that it would be better to have fixed laws than arbitrary ones, and to make a tabula rasa of their government?

We do not know anything about these revolutions, however, except that they occurred. That is unfortunate for the philosophy and science of today—an irreparable misfortune, for the little we know about the island causes us keenly to regret what we have lost.13

The African Atlantis had, therefore, all the best-founded entitlements to the credence and renown of history, our study and our admiration, or at least to our curiosity.

But where is it? What became of it?

“Atlantis disappeared in the space of a single day and night, under floods and ea

rthquakes. It is buried at the bottom of the sea.”14

In what time?

History does not say. But it must have been in a very distant era, since no other monuments, documents or reports of Atlantis existed other than a few volumes mysteriously buried in a library in Said in Egypt, where only a few scholars, of whom Solon was the first, discovered them, and which have not survived to our era.

Fortunately, their civilization and their sciences were not extinguished with them. They had spread them far and wide before dying. There was also their name…but so many centuries have passed over it, so many upheavals followed in their empire, so many barbarian feet trampled it that it was lost in the desert. As Citizen Bailly puts it, no more than an indistinct echo of it was any longer heard; it was no longer understood as anything but the memory of a dream.

That, I repeat, was a great misfortune!

Then again, perhaps the Atlanteans were, after all, like our noble and ancient families of the Middle Ages, who did not know how to write. Fully occupied with living as great lords, with fighting and conquests, and of finally settling here or there, according to the needs of their population, perhaps capriciously and perhaps also in accordance with points of honor, such as they were reckoned in the mores of antiquity, perhaps the Atlanteans could not write.

II. The War of the Gods

About three thousand five hundred years before our era—which is to say, more than a thousand years before the deluge—the Atlanteans were in the full flower of their growth. Their feats of arms, which had been numerous and brilliant before, were immense in those times, permitting them to consolidate the large-scale conquests that they had made in all parts of the world.

Thus, they had tributaries everywhere; they had founded substantial colonies everywhere, establishing the supremacy of their tactics, their courage and their civilization.

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge