- Home

- Hippolyte Mettais

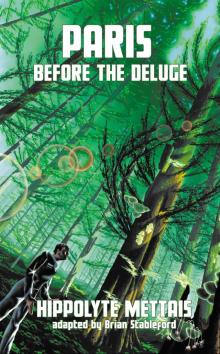

Paris Before the Deluge Page 21

Paris Before the Deluge Read online

Page 21

Chephren knew that; his thoughts were magnified to the same extent. He considered himself in consequence as the savior of the name of the Pah-ri-ziz, as the leader of a creative colony whose mission was to resuscitate a people that had just died, and he prepared for the future by organizing the present seriously.

In the midst of the incredible chaos that the Deluge had made, the ark appeared to be the only habitable place in Lutecia. Everyone made the best of it while they waited for the soil to be cleansed, for the infection produced by the cadavers that were burned and by the stagnation of the waters, some of which disappeared of their own accord and others with assistance from laboring hands, to become harmless.

Families were then formed. The projected marriages of Atlas and Mo-kie-thi finally took place; the saddened Chemis decided to remain the sister of the man she had believed to be her fiancé, until the law of Sylax afflicted her, if the law of Sylax were to be retained. Chephren and Nirvana remained isolated, Nirvana regretting the past bitterly, the philosopher irritated by not seeing the transformations for which he had been preparing so long advance more rapidly.

One day, he renounced them, and on that day he opened the doors of his ark and released all the animals that he had collected into the midst of the fields and the waters. But it was not without a great chagrin that he took that resolution, for all his scientific dreams were broken then, in a single instant: all the illusions he had caressed for such a long time, and all the progress that he had already made; in sum, the fruits of all the works most dear to him.

In consequence, he found thereafter an immense void around him; his life languished, his energy ebbed away, his brightest hopes for the future were extinguished one by one. He was dying of idleness, retreat and ennui.

Every day he wandered on his own in the fields, over the hills, on the seashore and along the banks of a few rivers that the deluge had created. He liked, most of all, to go back to his old abode, on the land that he had sanitized with so much effort, in the heart of which he had formed his projects and seen them grow so promisingly, even though it was not as he had left it.

The deluge had made it into a gracious island by creating a beautiful river whose two parted arms embraced it in its entirety, coming together again at its two extremities and continuing their course into the distance. He called that river the Sequan, in memory of the Sequanian Sea that had almost bathed the walls of Lutecia before the recent inundation, but which had retreated several leagues.

The philosopher spent entire days there, sometimes gazing into the distance to see whether, by any chance, one of the animals that he had looked after for such a long time and then set free would finally offer him a head that he had longed to see, an arm that he had seen in the process of formation, or a leg that he had once seen almost perfected. Then he looked into the depths of the waters, in search of the same images—but he never saw anything but his own, and he sighed.

One morning, however, his heart quivered with pleasure. He arrived on the bank of the river, his eyes searching the distance as usual, when he thought he had perceived something unusual on the other bank: something half-buried in the mud and the reeds—an animate being, for it was moving. His anxiety became extreme; the ardor of his rowing was unparalleled. In a matter of seconds, he was on the other bank.

O prodigy! What he had seen was not a dream or a hallucination; there really was an animate being there: a human being. Not everyone had perished, then, under the waters of the deluge! But yes, he was sure of it; they had all perished, except for the guests of his ark.

The face of the being was beautiful, well-proportioned; hair, abundant but short, ornamented the head; the form was female. He held out his hand; she took it, pulled herself out of the mud and stood up in front of him. Her arms were perfect, except that one of her arms terminated in a flipper; her feet were supple, but the slender toes were linked together in the form of a fan, suggestive of some vestige of the limbs of a marine animal.

A suspicion suddenly passed through the philosopher’s mind; he directed his gaze ardently toward the breast of the transformed being, where he recognized a symbol that he had once engraved.

He had succeeded, then! He had finally caused a creature to pass from one species to another; his secret was thus complete.

O Plunos! Plunos!

How he regretted, at that moment, the death of the unfortunate Dr. Plunos. How he regretted the destruction of Lutecia, its academicians, its scientists! He had discovered an immense secret, he had resolved a capital problem, he had found the secret of the creation of humans, and no one would know except for a few people who did not care.

But if it was written that the secret of the creation of humans would be revealed to the philosopher Chephren, it was also written that the secret would die with him.

XXI. The Last of the Pah-ri-ziz

A year after the philosopher Chephren’s precious discovery, the whole of the little colony was strolling along the bank of the river Sequan one day. It had already increased by a few members, who were, it is true, only in the cradle. Even the god Chephren was a father twice over, and, grave as he was, he smiled lovingly at a spouse who was doubly dear to him because she was the work of his science.

Atlas, whose eyes were directed upriver, discussing joyfully with Ormuzda how far his gaze extended, suddenly perceived several black dots in the distance that were floating on the waves, soon increasing in such a way as to allow the deduction that they were advancing toward them.

The walkers were somewhat anxious at first; then curiosity gripped them, and then the desire to find themselves in the presence of the beings coming toward the, who were perhaps going to put an end to their isolation—for there was soon no more doubt that they were humans, traveling over the water by means of oars.

They were indeed humans, and humans in considerable numbers, manning boats made of tanned animal hides disposed over simple wickerwork frames, but solidly fitted.

The travelers approached the bank without frightening anyone, for they made no hostile demonstration. They were nearly naked, but around their loins they wore garments of animal hide or fabric, retained by a thong passed over one shoulder like a bandolier. All the visible parts of the body were tattooed with different symbols. Their hair was long and loose, ordinarily thrown backwards. They were armed with arrows and clubs, a few even had swords; each of them wore a long and narrow buckler on the left arm, to protect them in the event of combat.

They were obviously warriors, but in the midst of the warriors there were women and children. There were priests clad in long white robes, wearing crowns of oak-leaves on their heads and carrying bouquets of mistletoe. They called themselves Druids.

The Pah-ri-ziz had before their eyes an emigration of people who were evidently seeking in a corner of the globe where they had not been born a refuge because none was any longer to be found in their birthplace, or because their vagabond temperament prompted them to seek further afield.

Before any man had set foot on land, a druid advanced to the prow of a boat, raised his eyes to the heavens, and then, extending his bouquet of mistletoe toward the ruins of Lutecia, he said in a loud and inspired voice:

“In the name of Ogmius and Hesus, we, the glorious Galls,29 have come from the extremities of the Orient into the places where our forefathers were, to take possession of their heritage. To you, sovereign Spirit, the first fruits of the blood of this people, whom we have just conquered, and who will be our slaves.”

At the same moment, loud inarticulate cries resounded in all the boats. Hu, the great chief of the warriors, who was standing beside the priest, drew his bow, which he aimed toward the bank. That movement, which not all the members of the little colony saw, but which Ormudza observed, frightened the young woman, who threw herself in front of Atlas with one bound, and then fell dead in her husband’s arms. A flint-tipped arrow had pierced her heart.

That death was the signal for a horrible carnage, for at that moment the traveling

warriors leapt ashore. Atlas, as furious as a wounded lion, hurled himself upon them; he seized a club and massacred everyone that came within range of his blows until, overwhelmed by numbers, he fell, never to rise again.

Less vigorous than him, but as ardent in the attack, his companions fought desperately. But what could they do against that host? They were slaughtered.

The fall of Chephren drove his companion crazy. As impetuous as a tigress, she leapt into a boat that was about to land and made superhuman efforts to overturn it in the waters of the river. Unable to succeed and seized by the men—who, respectful of the blood of a woman, dared not strike her—she hurled herself into the river, dragging several of her enemies with her, and did not reappear.

No one any longer remained on the bank but Ludia and Chemnis, who were mad with terror, and the infants, whom the cruel visitors had not immolated. Of the Pah-ri-ziz, only the philosopher Chephren was not yet dead. He was lying on the ground. A Druid was by his side, bandaging his wound with a rare sentiment of pity. He had declared him to be his guest; no warrior dared any longer to touch him, for he was not an enemy from then on.

The Druid, who was a scholar, a desirous man, a seeker of the truth, believed that he had found in Chephren a man precious to the studies he was pursuing. It was at his instigation that the Galls had ventured so far. He knew from the traditions admitted by the Gallic tribes that lived on the shores of Asia that his forefathers had founded settlements in Europe. Where, he did not know, but he wanted to know, and he had drawn an entire tribe of his brethren in his wake.

The emigrants had not found in their passage the island of the Teutchs or Sequania, which perhaps might have retained them if the deluge had not carried them away. They had, therefore advanced all the way to the Atlantis of the Pah-ri-ziz, and, an unexpected joy, they had found that the land was fecund in scientific secrets, for which they still had one man to reveal to them.

Thus, the Druid had Chephren taken to his tent. There he gave him all the cares of his art; he lavished on him all the secrets of medical science that only the Druids practiced.

In spite of the sufferings he endured, and in spite of the hatred that he was obliged to bear toward that barbarian horde, he did not refuse to answer his protector’s questions. He even appeared to obtain some relief from his troubles in talking about the past. He therefore told him everything he knew about the Atlantis of the Pah-ri-ziz, its modest and unfortunate origin, its successive and glorious growth, its grandeur and its decadence, its virtues and its faults, and then its final revolution, and finally its destruction by the waters of the deluge.

He even told him about the hopes of his philosophy, himself, the marvels of his ark, the happiness for which the little colony of the Pah-ri-ziz had still hoped, in the midst of the terrible catastrophe that had struck their fatherland, when the Galls descended upon them.30 He was about to tell him about the miracle of the transformation of animal species when an incessant cough took him by surprise, and then fits of vomiting blood, in the midst of which he died.

The Druid was heart-broken; he wept bitterly for the loss of the friend he thought that he had made.

Meanwhile, the victors had drawn lots for Ludia and Chemnis, who were taken to the tents of their new masters, where they pierced their hearts with arrows in order to be free again.

The children remained orphans, but the Galls raised them with care, and they subsequently became the glory and honor of their adoptive fathers, who settled permanently in the Atlantis of the Pah-ri-ziz.

Their new fatherland then took from their name the name of Gallatchd, later to be known as Gaul.

Notes

1 The introduction to the Black Coat Press edition of The Year 5865 (ISBN 9781612271002) contains a summary of what is currently known about Mettais’ life and career, which there is no need to repeat in full here.

2 Black Coat Press, ISBN 9781934543030.

3 Included in The Human Ant, Black Coat Press, ISBN 9781612273235.

4 Black Coat Press, ISBN 9781612271613.

5 Black Coat Press, ISBN 9781612272801.

6 5810 – 1866 = 3944. This differs from James Ussher’s 1650 calculation by sixty years, but that discrepancy has a Biblical basis in the textual ambiguity of the date of Abraham’s birth, so some alternative calculations do offer 3944 B.C. as the likely date of Adam’s creation, alongside numerous other figures based on different estimates and interpretations.

7 The insistence that climate was an important factor in determining theological beliefs was promoted by several 19th-century French writers, but is particularly evident in the works of the positivist Auguste Comte (1798-1857).

8 In English versions of the scriptures it is the “fleshpots” of Egypt that the Children of Israel regret, not, as in French versions, the onions, but in translating from French to English rather than from Hebrew, it seems more appropriate to reflect the French priority.

9 The lunisolar period is actually 532 years in the Julian calendar, but it was often mistakenly reckoned as 600 years, including a much-publicized assertion by the astronomer Giovanni Cassini (1625-1712), allegedly based on Josephus, which was cited by Buffon and Bailly, among others.

10 Author’s note: “If my book L’An 5865 is read attentively, it will be seen that I have not wanted to say about history anything other than what I say here.”

11 Author’s note: “The Atlanteans, says Solon and Plato with him, were already a great people nine thousand years before the voyage of the former to Said in Egypt—which is to say, about 600 B.C.”

12 Author’s citation: “‘They [the kings of Atlantis] also reigned over the entire region from Libya to Egypt, and over the coast of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia.’ Plato, Dialogues of Timaeus and Critias.”

13 Author’s citation: “‘There is a misfortune common to noble and ancient families. The testimony of historians has been effaced, the thread of tradition has been broken in the deserts formed by war and the centuries of ignorance that are the deserts of time. But a confused notion remains, a few facts engraved in memory, the duration of which advertises the importance of the truth. A long memory, the memory of humans, is something else entirely: I give great weight to ancient traditions preciously conserved by a sequence of generations.’ Bailly, Lettres sur l’Atlantide.”

14 Author’s citation: “Plato, Dialogue of Timaeus.”

15 Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat (1788-1832) was the most important sinologist of the 19th century; the chair of Sinology at the Collège de France was created for him. His “Observations sur le religion samaneene” is contained in Mélanges Posthumes d’Histoire et de Literature (1843) and might be apocryphal, as the cited document obviously is.

16 Modern estimates prefer death dates in the fifth century B.C.

17 Author’s note: “This island must be in the Rhine, near the mouth of the Lippe. Everyone knows that Teutchs is the original name of the Germans. In the second antiquity they were called Ker-mann, Wher-mann and finally Germans.” The word that would nowadays be rendered Deutschland is rendered as Teutchsland in a small number of 18th and 19th century German sources.

18 Author’s note: “See Tacitus.” The reference is to Cornelius Tacitus’ De Origine et situ Germanotum [On the Origin and Condition of the Germans], written at the end of the first century A.D. but lost and rediscovered in 1425. Mettais had no way of knowing that it would be adopted long after his death by the Nazis as a pillar of their sense of national identity, thus ruining its reputation.

19 Author’s note: “Sequan means serpent in the language of that people, as in that of the Gauls, who probably borrowed it from them. I apologize here for all these little notes, and hope that I shall not be accused of pedantry with regard to my subject. My intention is merely to prove the respect that I have for the truth, and that if I consent to group facts, perhaps arbitrarily, it is not purely for amusement or by virtue of eccentricity. My thinking is very serious and always respectful of the instruction of science.” In fact, Sequan

i was a name given by Julius Caesar to one of the Gallic tribes living to the west of the Jura mountains. He also gave the name Sequana to the River Seine; although there seems to be no connection between the attributions, Mettais subsequently goes out of his way to contrive one.

20 Author’s note: “It is probable that this location was the present-day Switzerland. Scientists say, in fact, that in the first antiquity Switzerland, covered in water, formed a sea.”

21 One of the literary essays in calculated myth-transfiguration that Mettais would have had available to him when he wrote the present text was Edgar Quinet’s Merlin l’enchanteur (1860; tr. as The Enchanter Merlin, ISBN 9781612273037), which also waxes lyrical on the subject of “the unknown God” whom Merlin prefers to all those specified by religious dogma.

22 Mettais’ political pamphlet, published not long before his return to literary work, was Des Associations et des corporations en France (1859)—a defense of what would be called trades or labor unions.

23 Author’s note: “Noah, in the Hebrew language, similarly means something like ‘recluse.’ I leave it to the reader to decide whether the name and deeds of Noah have any analogy with the facts we are relating. It is permissible to wonder, when we know how many curious and sentimental legends born of perfectly natural and simple facts our forefathers have transmitted to us that have reached us through the ages with along all the marvels of their naïve beliefs.”

24 Author’s note: “The Atlantis of the Pah-ri-ziz being recognized as France and Lutecia as Paris, it is not improbable that Chephren’s retreat occupied the territory of our Île de la Cité.”

25 Mettais appears to have forgotten that the year 2348 B.C. was actually the year before 2347 B.C., not the year after.

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge