- Home

- Hippolyte Mettais

Paris Before the Deluge Page 18

Paris Before the Deluge Read online

Page 18

The peasant made a gesture that implored extenuating circumstances for an action of dubious probity. “The little boy, oh, damn it…but the necklace, I kept it, because one never knows, and I said to myself: what if, one day, I were to run into the man who confided him to me? For the boy, I’ll always be able to find him, for I’ve taken precautions for that, and the little girl too…oh, I didn’t tell you that there was also a little girl, but she didn’t have a beautiful necklace, only a little red ribbon from which a lead medallion was hanging, which I also have there.”

“It’s just that it’s very fine, your necklace,” said Ormuzda, who could not weary of admiring it.

“So much the better!” Ypsoer replied, going into the cottage after carefully closing the little box, in which he had replaced the necklace.

The two young people followed him. Ypsoer approached Ludia respectfully, very unsure as to the best means of getting her to accept his present. To that effect he took detours in which he alone could glimpse the path of which he was in search, remarking without rhyme or reason on the good weather, the quarrels of the neighborhood and curious anecdotes concerning the region.

“Have you heard the big news, my lady,” he said, suddenly changing the subject again. “Our manor house…I say our because it’s in our neighborhood…although it isn’t, because it’s on the other side of the mountain…anyway, it doesn’t matter…what I mean is that our manor, which has been abandoned for months, has a new proprietor, who got it very cheap...”

“Really?” Ludia replied, with all the more interest because she was suspicious of the merit of the new owner, whom she did not know but could measure by the fact that he had obtained the property of an exile very cheap. She was quite familiar with the law of confiscation.”

“Yes, and I’ve even seen him,” said the peasant. “He’s a big fellow with strong arms—stronger than mine—and a dark, hard face...”

“What’s his name?”

“Ah! Well, I don’t know…that’s because, you see, I have no memory, I only recall one thing in my whole life...” Ypsoer looked at his listeners, whose attention encouraged his confidence. “Yes, I only recall one thing in my whole life. It was one evening…but it wasn’t here, it was a long way from here…you see, I was born in this valley but I traveled a little to search for what I haven’t found, and then, as they say…the swallow always returns to it’s nest…I came back, and, well, one evening an invisible hand put a very small child into my hut...”

“Ah!” said Ludia, becoming more attentive.

“Yes, a little child who had a pretty necklace around his neck, so pretty...”

“Let me see!” said Ludia, sharply, reaching out as Ypsoer made as if to present the little box to her.

“Here it is,” said Ypsoer, opening the box himself, and adding: “And if it’s agreeable to you, my lady...”

Ludia turned the necklace over and over. Her eyes were shining with pleasure and hope, her face blossoming. She smiled blissfully. She took Ypsoer’s hand and squeezed it convulsively as she drew him toward the door of the cottage.

“Who gave you this necklace?” she said to him, mysteriously. “Would you recognize him again?”

“Well, no…since I didn’t see him.”

“That’s true,” said Ludia.

“But I can tell you that it was sixteen or seventeen years ago, at least, if I remember correctly.”

“Nineteen years,” said Ludia, to herself, and added: “And the child who wore the necklace—would you recognize him?”

“Oh,” said Ypsoer, smiling, “the child was so small, so small…however, my lady...” He went back into the room and headed toward Hyperion, whose arm he took. “I made a little mark on his arm...” So saying, the peasant casually lifted up the sleeve of Hyperion’s mantle, in order to indicate the place where he had engraved the sign. Then he stopped in amazement, looking at Hyperion and Ludia.

“A mark like this,” he added, finally, pointing with the tip of his finger at a small irregular cross that was imprinted on the young man’s arm.

Hyperion could not help smiling at the amazement of the peasant, who was still dazedly contemplating the sign that he thought he recognized, while Lady Speos and Ormuzda stared at their invalid with an indefinable bewilderment, from which they were extracted by a sharp exclamation from the door of the cottage, which opened at that moment.

A vigorous young man with enormous shoulders was standing on the threshold. All eyes turned to him.

“My very humble respects to you, sir,” Ypsoer said to the newcomer, bowing deeply toward him. To Ludia, he said, in a low voice: “That’s the new owner of the manor.”

“I’ve come to discuss very serious business with Lady Speos,” said the visitor, in a severe voice. “There are so many people here that I’ll come back another time, unless the lady consents to come to the manor, where we won’t be disturbed, and where she’ll find friends.”

“Lady Speos will not go to the manor,” said Hyperion, who was making an extraordinary effort to give his voice an intonation befitting the indignation that was rendering him furious.

“My lady will come,” replied the importunate visitor, calmly, “because it’s a matter of the life or death of someone who might be dear to her.” Looking at Ormuzda, he added, emphatically: “As well as others...”

“Yes, my lord, I’ll come,” said Ludia, who seemed breathless. She looked determinedly at Hyperion and Ormuzda, who seemed consternated by the promise she had just made and added: “And I’ll go alone,” as she watched the lord of the manor draw away.

XVII. The Two Crosses

That same evening, Ludia left the little house on her own and climbed the mountain through the tall trees that separated the valley from the manor. Five o’clock had just chimed on the village’s communal tower. The night was beginning to get dark beneath the thick fog of the marshes; the chill was sharp; the wind was whistling through the crowns of the oak trees, whose desiccated leaves were quivering in a magical manner.

Glacial and murderous winter was beginning to make its first assaults felt in the valley, which it exhausted like an unjust despot, leaving all the charms of a mild temperature to reign in neighboring regions.

The lady was impatiently awaited at the manor, where everything seemed to be silent. In a large drawing room with rich wall-hangings, decorated with precious furniture and filled with portraits of aristocratic families, there were three people who might have seemed out of place there.

One of them was admiring, distractedly, the luxury and elegance of the drawing room, which the former owner had left in a perfect state of conversation, perhaps out of generosity, but more likely having been taken by surprise. He was sprawled negligently in a large light-backed armchair, waiting for someone to speak to him.

The other two people formed a charming couple. There was a young man—Lady Speos’ visitor—still pensive, and only relaxing slightly under the child-like caresses of a young woman who was striving almost in vain to cheer him up. He contrived a slight smile, but the smile was so distracted that it was easy to see that other thoughts were preying on his mind.

“Do you want anything else, Atlas?” asked the young woman, in a tender voice.

“No, nothing, Chemnis,” the young man replied, “for I believe that you’re going to be happy soon.”

“Happy! But I always am, as long as you don’t leave me... You’re laughing at that, Nimrod?” she added, addressing the third person, whom she had seen smiling.

“No,” Nimrod replied. “I’m only smiling—and I say that before anything else, Atlas has a duty to the fatherland, which has rewarded him generously for his devotion; he has a duty to the club that has given him a place on the great government council, in spite of his youth; and he has a duty to the future.”

“Yes, I have a duty to the future,” said the new lord of the manor, enthusiastically, suddenly becoming animated. Then he got up and went to the fireplace, on the mantelpiece of which

he leaned, presenting his back to the fire, while Chemnis, whom he seemed to have dismissed, left the room in order not to witness a greater proof of indifference.

“What are you thinking about, then?” said Nirmod, who seemed to have been waiting until they were alone to make his reflections. “Honors? You have them. Riches? You no longer have any lack of them. Love? That little Chemnis loves you dearly. But you’re thinking about Ormuzda, who didn’t love you before and who detests you today, because you’ve put her father in prison on a charge of plotting against the security of the State.”

“It’s you who’ve done that,” Atlas retorted, disdainfully.

“Me? No—I’m not powerful enough for that. I’ve advised, I’ve acted, I’ve undertaken commissions, I don’t deny, but the essential word was pronounced by you.”

“Well...,” said Atlas, frowning.

“You’ve done well, by Sylax! But it’s only partly succeeded. I would have liked his property to revert to you...”

“Never!” said Atlas, disdainfully.

“Or to me,” Nimrod continued. “The State has kept it, unfortunately. I’m afraid that it will do the same with that of Mo-kie-thi, which I coveted. You recall Mo-kie-thi—that old friend of Speos whom you placed on the proscription list the other day, like his friend Nirvana, who is speaking out against my master, who refuses to recognize him in order to establish his identity—which establishment seems to me to be rather difficult, as there are only three people who would dare to testify against Speos: Nirvana, Ludia and me.

“After all, I can’t see what Lord Speos has to gain. It’s quite possible that if Mo-kie-thi isn’t recognized, the State—which is hungry—will consider him proscribed, and confiscate his wealth. If, on the other hand, Mo-kie-thi is recognized, his wealth will revert to him by right, but only to pass, in spite of Speos, into the hands of the Republic—which, I believe, has a list of charges ready to launch against his culpability, which might well resemble Nirvana’s. Oh, the Republic understands; it knows that those people never reform, no matter what they say.”

“Well,” said Atlas, finally emerging from the profundity of thought into which he had been plunged, “I wasn’t thinking about any of that.”

“Oh,” said Nimrod. “What were you thinking about, then?”

“It seems to me that I’ve lived here before—in the Valley of the Desert, at least.”

“Bah! I don’t think so.”

“Yes, when I was very young, with a peasant by the name of Ypsoer.”

“What! Ypsoer!” said Nimrod, fixing Atlas with his lynx-like eyes.

“Ypsoer will tell us himself soon, for he’s coming back.”

“Ah! You’ll want to be alone with him, then, and I’ll leave you,” Nimrod said, turning his head anxiously in the direction of the entrance door, where he had heard a sound, and slipping out of the room on the opposite side.

The door of the drawing room opened at the same time. It was Lady Speos. She came in with the assurance of a person who conserves a long superiority over the person she is visiting, but with the modesty of a woman who understands that it is necessary not to be arrogant in order to prevail.

“Please sit down, Madame,” said Atlas, very affably, offering her the armchair of honor, “And let’s get straight to the point. It appears, Madame, that you have appointed yourself the guardian of Lady Ormuzda?”

“Yes, my lord, since you have separated her from her father,” Ludia replied, firmly.

“And your advice is graciously welcomed by her?”

“She is as submissive as a meek child; in any case, her life is so pure...”

“So pure! I believe it, Madame. However, she lives under the same roof as a young man whom she probably loves...” Atlas grimaced resentfully.

“Oh, my lord—a dying man...”

“Yes, but a young man.”

“A young man from whom I cannot separate myself, my lord, for we owe, by way of reparation, at least as much care as the evil we have done…and then,” the lady added, with great emotion, “I’ve adopted him as my son...”

“That’s all very well,” Atlas went on, sharply, “but the Lady Ormuzda...”

“Think, my lord! No father any longer...”

“But if he were returned to her...”

“May the three divine friends hear you!” Ludia exclaimed.

“On one condition, however,” said Atlas, in a low voice, turning his head in order not to meet the eyes of Lady Speos, who was looking at him in bewilderment.

“What condition, if you please?”

“That of marrying a member of the present government,” replied the Me-nu-tchean parvenu, severely, seeking to disguise the pettiness of his condition with the gravity of his voice.

“You, perhaps, my lord?” asked Ludia.

“Me, if you please, my lady.”

“That’s all right, Lord Atlas,” said Ludia, getting up to leave. “Ormuzda will do that.”

It was just in time, for Ypsoer, who had been kicking his heels for a quarter of an hour at the door, wondering whether he could go into the drawing room in the same fashion as he was accustomed to going into his neighbors’ houses, had become impatient and opened the door at that very moment.

“Stay, my lady,” said Atlas to Ludia, who was trying to leave. “It’s late, at least in your valley; I only have a few words to say to this man, and then I’ll escort you down the mountain.”

“Thank you, my lord, but I’m not afraid.”

“Don’t worry, my lady,” said the peasant. “My lord needn’t go to any trouble; I’ll take you back myself.”

Ludia hesitated, perhaps not entirely confident, in spite of what she said. In response to a further invitation, she decided to stay.

“Ypsoer,” said Atlas to the peasant, “someone once entrusted a child to you.”

“Two, my lord—a little boy and a little girl.”

“What did you do with them?”

“My lord,” Ypsoer replied, greatly embarrassed and lowering his head. “I could no longer feed them...”

“You abandoned them?”

“That’s true, my lord, but...” Ypsoer turned to Ludia. “But I believe, my lord, that the little boy has been found.”

“What!” said Atlas, with an anxiety suggesting that what the peasant had said had cast a disappointment into his heart.

“Yes, can you imagine, my lord, that a little while ago, in order to show my lady where I had put a sign on the arm of the child entrusted to me, I lifted up the sleeve of poor Lord Hyperion’s mantle, just like this...” He also took hold of Atlas’ sleeve, who lent himself readily to the demonstration, and lifted it to. “And there…damn!”

The word suddenly froze on Ypsoer’s lips. He had found on Atlas’ arm the same cross that he had seen on Hyperion’s.

“That’s strange!” exclaimed Ludia, getting up precipitately and seizing the Me-nu-tchean’s arm avidly.

“I know one thing,” the peasant said, then, “which is that I did what many others did—I made a cross, not knowing how do anything better. Not that I mean that my lord…but that really is my cross.”

“And how long ago was this?” asked Atlas.

“Eighteen or nineteen years...perhaps eighteen…perhaps seventeen,” he added, changing his mind, truing to please his listeners, who were looking at him with anxious eyes, whose aspirations he did not understand.

“Not nineteen?” asked Atlas.

“Damn! Perhaps, my lord…I’ll ask my wife,” Ypsoer replied, no longer knowing what to say.

Atlas greeted the peasant’s uncertainty with a gesture of discontent that frightened the poor man, while Ludia lost herself in a void of hopes that she had thought filled in, but which she suddenly saw opening up in front of her once again.

She left, in consequence, full of discouragement, accompanied by Ypsoer, who was biting his fingernails at not having pronounced firmly the number nineteen, which seemed now agreeable to the new lord of the manor

.

A moment later, Atlas looked up in order to ask further questions, but found himself alone. He had not heard his visitors’ farewells. He fell into his armchair, as if exhausted, striking his forehead, grinding his teeth and cursing the fatality that weighed upon him.

Several times he had thought that he was on the point of discovering his birthplace; just now he had caressed that hope with delight, but it had just vanished again. It seemed to him, therefore, that he was destined to be the continual victim of cruel phantasmagorias directed by a power that laughed at his own.

For an ambitious man, however, Atlas’ luck might have seemed excellent. To have departed from nothing in order to arrive at the height of grandeur—what more could he desire?

Nor did he desire anything—except for a little love on the part of Ormuzda. The favors of fortune were not those he had sought; it was not for his own sake that he wanted to find traces of his birthplace, but for the sake of that love.

Great things and great men often have an origin that is not the most pure. It is almost always personal interest, the stimulation of egotism, that raises a man out of his sphere and causes him to undertake striking deeds. But when the result is good, say men of conviction, what do the means matter?

Perhaps that equivocal maxim was the one that Atlas had adopted. At any rate, it presented nothing repulsive in his case, for, in spite of appearances, Atlas was not one of those grim and bloodthirsty democrats whose memory always causes tremors in all ages. A little ambition, quite natural at his age, and a great deal of love, had made him what we see.

For the harm that he did, one might reproach necessity more than him, and the blind force that continues indefinitely the initial impulsion given to a project whose twists and turns one has not always calculated. He was, in any case, no more guilty than the society that had made the privileged castes of which he was the victim, and no more than Ormudza, whom he loved and who did not love him. If he fought harshly against her, whose fault was that? If he was perhaps unjust, tyrannical, even—alas!—savage…he loved her so much...

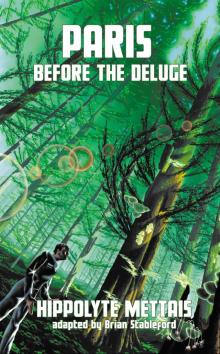

Paris Before the Deluge

Paris Before the Deluge